Why recovery began with a wristwatch, a packing list, and a belief that creation is an act of defiance.

When people ask how I got into this line of work, software engineering, RevOps development; I don’t always know where to start.

Do I say it helped me fight anorexia? Do I say it helped me survive?

The truth is: this story begins in rehab.

Creation vs. Destruction

When people picture a “tortured artist,” they conjure Vincent van Gogh: the one-eared self-portrait, the sunflowers, the haunted brilliance.

But Starry Night wasn’t painted in chaos. It was painted in treatment. Van Gogh created it while in a rehabilitation facility, gazing out the window, combining memory with the present.

The most beautiful thing he made came not from destruction, but from the slow, difficult work of trying to heal.

At The Renfrew Center, I heard this echoed in Kyle’s art therapy classes. Every session began with his mantra:

“Creation is the opposite of destruction. To create, you must heal. And that healing is the sacrifice required to make great art.”

And in that spirit, while I painted and sketched and journaled, my truest masterpiece wasn’t on a canvas. It was the systems I built to hold me together.

Renfrew’s Spring Lane campus is tucked into a wooded estate just outside Philadelphia. It was the first residential program in the U.S. built specifically for eating disorders. Not a sterile hospital, but a place designed to feel like a home.

There, I was one of about 45 women ranging in age from teenagers to grandmothers. We shared meals, groups, vitals checks, therapy sessions. We filled out acronyms like ARCs (Antecedent, Response, Consequence) and FEJs (Food Emotion Journals) until the pages blurred.

Renfrew treats anorexia, bulimia, binge eating disorder, ARFID — but more than that, it treats the grief, trauma, and perfectionism that often come with them. It’s not easy work. But it’s work that saved my life.

The Watch That Fed Me

One of the cruel effects of long-term anorexia is losing your hunger cues. My body didn’t signal hunger. My brain didn’t trust food.

So I bought a vibrating wristwatch. At first, it was just an alarm to get me up for 5 a.m. vitals without waking my roommate. But soon, it became something else.

I programmed it to buzz at breakfast, mid-morning snack, lunch, afternoon snack, dinner, and evening snack. A rhythm, not a choice.

It was my Pavlov experiment: if dogs could be trained to salivate at a bell, maybe I could retrain myself to expect food at a vibration.

I wore it for the month of inpatient. For another month of virtual outpatient. And for a final month at home until, slowly, my cues returned.

It wasn’t elegant. But it was scaffolding. And scaffolding holds you up when you can’t stand alone.

Packing Fear Into a List

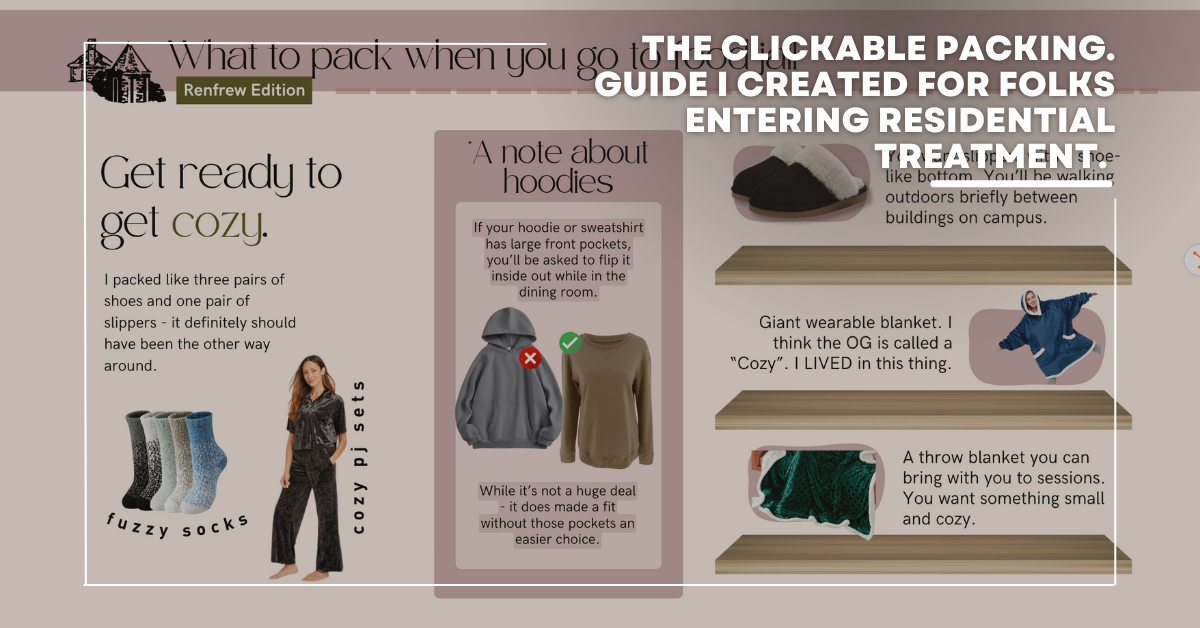

Near the end of my stay, one of my peers was being “leveled up” to the same residential program I had just completed. I remembered the fear of my own first night — Googling “what to pack,” finding nothing useful, having perfume confiscated as contraband.

I wanted her to walk in better prepared than I had.

So I built the Ultimate Packing Guide for Residential Treatment — a clickable list with notes and links. Plastic spray bottles instead of glass. Cozy socks. Journals. Small comforts that make a hospital room feel less like one.

I made it for her. Then shared it with the group. Eventually, with anyone who might need it.

From Paper Logs to a Recovery Hub

Residential treatment gave us one hour of phone time per day. All else was paper. ARCs and FEJs printed from Excel, filled out by hand, graphed by pencil. Recovery was already hard — did I really need to do arithmetic on top of it?

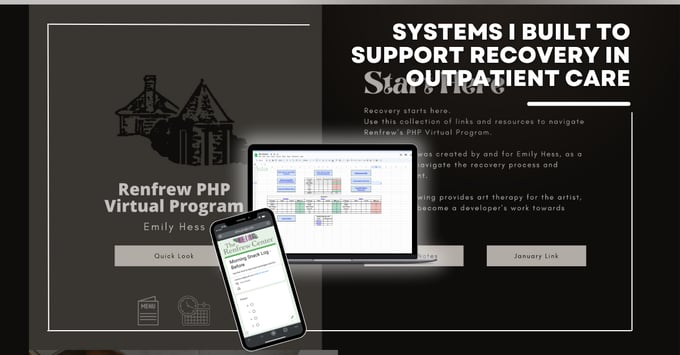

By the time I reached partial hospitalization (virtual, daily Zoom sessions), I was determined to change that.

I rebuilt the tools digitally:

- Google Forms + Sheets to log FEJs and ARCs, complete with auto-calculations.

- Automations that stored each entry in Drive, organized and shareable with my therapist and dietitian.

- Shortcuts on my phone that nudged me to log before and after meals — subtle reminders, not alarms blaring like I was still inpatient.

Then I built a full Recovery Hub website in Canva:

- One page for weekly Zoom links.

- One for my PHP notes.

- One for the UT Workbook.

- Links to my logs, surveys, and resources.

And finally, I trained two custom GPTs:

- The Frew Crew Menu Expert: fed with my vegetarian preferences, Meal Plan C+, and the Renfrew menu, it suggested meals and snacks to keep me on track.

- The Homework Assistant: trained on Renfrew’s UT model, my notes, and the program workbooks. It walked me through assignments when my brain froze.

It was part spreadsheet, part AI, part scrapbook. And it worked. My Recovery Hub was my Starry Night - born in treatment, fed by survival.

Returning to Work, Rewriting the System

When I stepped down from treatment, I returned to my role in marketing operations. In my absence, our systems had grown complicated, and the team was frustrated.

I looked at it and thought: I just built systems that kept me alive. I can fix this too.

So I started with sales and marketing. In six months, the chaos cleared, and the system finally worked the way people had hoped it would.

From there, I expanded into operations. Pulled every team into one framework. Built automations that gave people their time back. Proved that technology could adapt to humans; not the other way around.

And that’s how Markit began.

Why I’m Sharing This

No, my spreadsheets aren’t hanging in the Musée d’Orsay. But like Van Gogh, I learned that the act of creating — even a system — is itself an act of healing.

And that’s what I carry into my work today.

Because systems can save us.

In recovery. In business. In life.

I systematized my recovery. Now I help founders systematize their businesses — with the same philosophy:

- Structure that frees you.

- Reminders that support you.

- Processes that protect your energy.

If you’re here for recovery: Explore my Recovery Resources

If you’re here for business: Work with Markit

Either way, welcome. I’m Emily. And this is my story.